Теплопроводностью

называют свойство материала передавать

теплоту одной поверхности другой. Мерой

теплопроводности является коэффициент

теплопроводности λ,

представляющий собой количество тепла

(Дж), проходящее через стенку толщиной

1 м, на площади в 1 м2

за 1 час при разности температур на

противоположных поверхностях в 1 °C.

В

международной системе единиц измерения

коэффициент теплопроводности имеет

размерность Вт/м·°C.

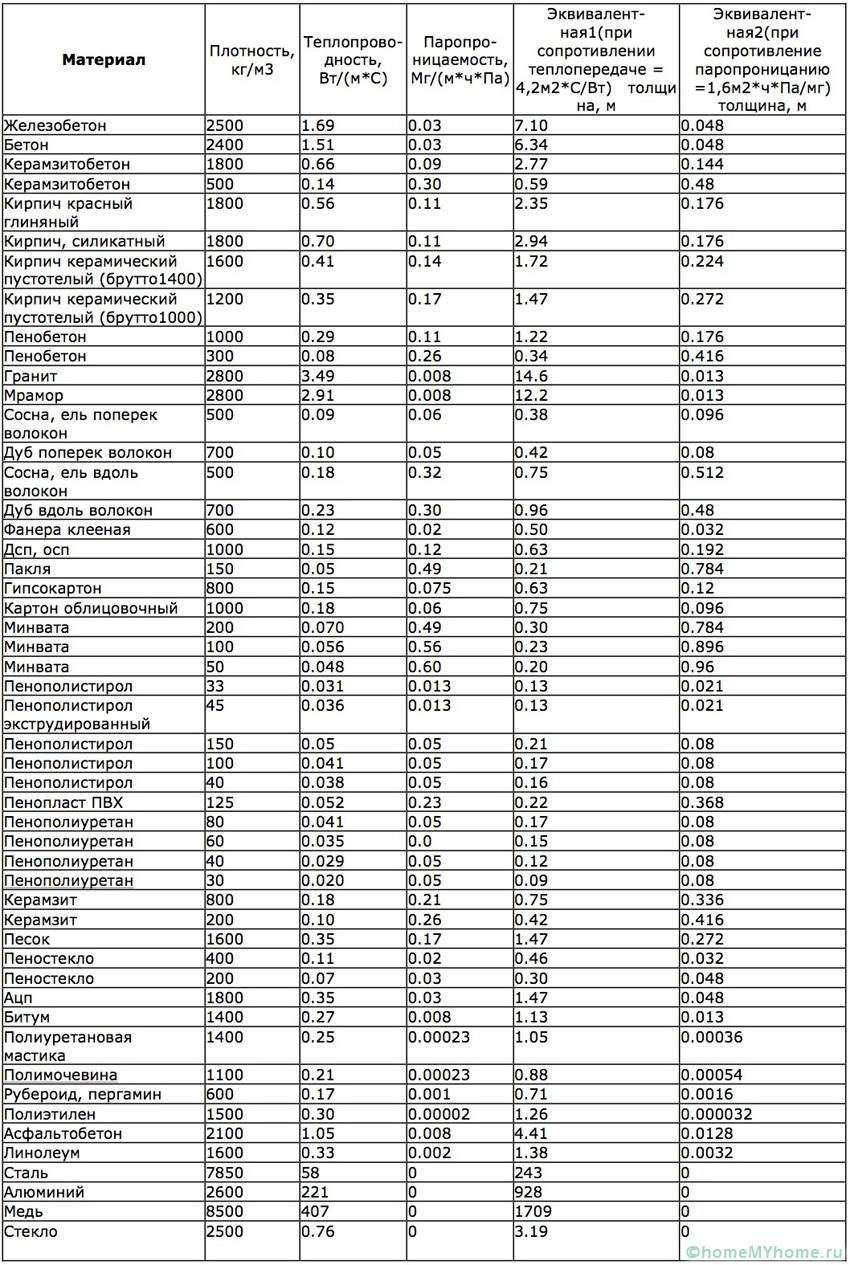

Значения коэффициента теплопроводности

(Вт/м·град) для некоторых материалов

приведены в таблице 1.2.

Коэффициенты

теплопроводности различных материалов

Таблица 1.2

|

Материал |

λ, |

Материал |

λ, |

|

Сталь Гранит Тяжелый бетон

Кирпич керамический Газостекло |

58 2,9 – 3,3 1,28 – 1,55 0,8 – 0,9 0,06 – 0,0 |

Воздух Вода Бетон легкий

Бетон Пенополистирол |

0,023 0,59 0,35 – 0,8 0,08 – 0,3

0,035 |

Основным

фактором, определяющим теплопроводность

строительных материалов, является их

пористость, что ясно видно из сопоставления

величин коэффициентов теплопроводности

воздуха (0,023) и плотного камня (2,9). Кроме

того, теплопроводность материала зависит

от температуры: при повышении температуры

теплопроводность λt

увеличивается (для температур до 100 °C)

при температуре материала t

с достаточной точностью можно вычислить

по формуле

,

(1.14)

где

λ0

– теплопроводность при 0°C;

β

– температурный коэффициент, β

= 0,0025.

При

более высокой температуре зависимость

(1.14) теряет линейный характер.

При эксплуатации

материала во влажных условиях воздух

в порах может быть частично замещен

водой, и теплопроводность материала

резко возрастает, так как теплопроводность

воды в 25 раз выше воздуха. При замерзании

воды в порах материала его теплопроводность

повышается еще в большей степени.

Теплопроводность

материалов можно приближенно определить

по величине его средней плотности с

графика, изображенного на рисунке 1.8.

ρ0,

кг/м3

Рисунок

1.8 – Зависимость теплопроводности

материалов от плотности:

1 – неорганические

материалы сухие; 2 – неорганические

материалы, насыщенные водой; 3 –

органические материалы

Кроме

того, зная значение плотности материала

(ρ0),

можно подсчитать его коэффициент

теплопроводности по эмпирической

формуле В.П. Некрасова:

,

Вт/м°C,

(1.15)

где

ρ0

– средняя плотность материала, г/см3.

При

расчете ограждающих конструкций

пользуются такой важной характеристикой,

как термическое сопротивление R,

м2°C/Вт:

,

(1.16)

где

δ

– толщина, м;

λ

– теплопроводность данного материала,

Вт/м°C.

По

результатам всех определений составляются

акт испытания материала и заключение

по нижеприведенной форме (таблица 1.3).

Акт

испытания

Таблица 1.3.

Наименование

материала________________________________

|

Показатель |

Обозначение |

Единица измерения |

Результат |

Заключение |

|

1. Средняя плотность правильной формы

неправильной

2. Плотность

3. Истинная

4. Водопоглощение

5. Водопоглощение

6. Водонасыщение

7. Коэффициент

8. Предел прочности

9. Предел прочности

10. Коэффициент

11. Коэффициент |

ρ0 ρ0 ρ ρи П W0 Wm Wн Км

Rсж.

Rсж. Кр λ |

г/см3 г/см3 г/см3 г/см3 % % % % б.р. МПа МПа б.р. Вт/м°C |

The thermal conductivity of a material is a measure of its ability to conduct heat. It is commonly denoted by

Heat transfer occurs at a lower rate in materials of low thermal conductivity than in materials of high thermal conductivity. For instance, metals typically have high thermal conductivity and are very efficient at conducting heat, while the opposite is true for insulating materials like mineral wool or Styrofoam. Correspondingly, materials of high thermal conductivity are widely used in heat sink applications, and materials of low thermal conductivity are used as thermal insulation. The reciprocal of thermal conductivity is called thermal resistivity.

The defining equation for thermal conductivity is

Definition[edit]

Simple definition[edit]

Thermal conductivity can be defined in terms of the heat flow

Consider a solid material placed between two environments of different temperatures. Let

According to the second law of thermodynamics, heat will flow from the hot environment to the cold one as the temperature difference is equalized by diffusion. This is quantified in terms of a heat flux

The constant of proportionality

The preceding derivation assumes that the

General definition[edit]

Thermal conduction is defined as the transport of energy due to random molecular motion across a temperature gradient. It is distinguished from energy transport by convection and molecular work in that it does not involve macroscopic flows or work-performing internal stresses.

Energy flow due to thermal conduction is classified as heat and is quantified by the vector

where the constant of proportionality,

In some solids, thermal conduction is anisotropic, i.e. the heat flux is not always parallel to the temperature gradient. To account for such behavior, a tensorial form of Fourier’s law must be used:

where

An implicit assumption in the above description is the presence of local thermodynamic equilibrium, which allows one to define a temperature field

Other quantities[edit]

In engineering practice, it is common to work in terms of quantities which are derivative to thermal conductivity and implicitly take into account design-specific features such as component dimensions.

For instance, thermal conductance is defined as the quantity of heat that passes in unit time through a plate of particular area and thickness when its opposite faces differ in temperature by one kelvin. For a plate of thermal conductivity

Thermal resistance is the inverse of thermal conductance.[6] It is a convenient measure to use in multicomponent design since thermal resistances are additive when occurring in series.[7]

There is also a measure known as the heat transfer coefficient: the quantity of heat that passes per unit time through a unit area of a plate of particular thickness when its opposite faces differ in temperature by one kelvin.[8] In ASTM C168-15, this area-independent quantity is referred to as the «thermal conductance».[9] The reciprocal of the heat transfer coefficient is thermal insulance. In summary, for a plate of thermal conductivity

The heat transfer coefficient is also known as thermal admittance in the sense that the material may be seen as admitting heat to flow.[10]

An additional term, thermal transmittance, quantifies the thermal conductance of a structure along with heat transfer due to convection and radiation.[citation needed] It is measured in the same units as thermal conductance and is sometimes known as the composite thermal conductance. The term U-value is also used.

Finally, thermal diffusivity

.

As such, it quantifies the thermal inertia of a material, i.e. the relative difficulty in heating a material to a given temperature using heat sources applied at the boundary.[12]

Units[edit]

In the International System of Units (SI), thermal conductivity is measured in watts per metre-kelvin (W/(m⋅K)). Some papers report in watts per centimetre-kelvin (W/(cm⋅K)).

In imperial units, thermal conductivity is measured in BTU/(h⋅ft⋅°F).[note 1][13]

The dimension of thermal conductivity is M1L1T−3Θ−1, expressed in terms of the dimensions mass (M), length (L), time (T), and temperature (Θ).

Other units which are closely related to the thermal conductivity are in common use in the construction and textile industries. The construction industry makes use of measures such as the R-value (resistance) and the U-value (transmittance or conductance). Although related to the thermal conductivity of a material used in an insulation product or assembly, R- and U-values are measured per unit area, and depend on the specified thickness of the product or assembly.[note 2]

Likewise the textile industry has several units including the tog and the clo which express thermal resistance of a material in a way analogous to the R-values used in the construction industry.

Measurement[edit]

There are several ways to measure thermal conductivity; each is suitable for a limited range of materials. Broadly speaking, there are two categories of measurement techniques: steady-state and transient. Steady-state techniques infer the thermal conductivity from measurements on the state of a material once a steady-state temperature profile has been reached, whereas transient techniques operate on the instantaneous state of a system during the approach to steady state. Lacking an explicit time component, steady-state techniques do not require complicated signal analysis (steady state implies constant signals). The disadvantage is that a well-engineered experimental setup is usually needed, and the time required to reach steady state precludes rapid measurement.

In comparison with solid materials, the thermal properties of fluids are more difficult to study experimentally. This is because in addition to thermal conduction, convective and radiative energy transport are usually present unless measures are taken to limit these processes. The formation of an insulating boundary layer can also result in an apparent reduction in the thermal conductivity.[14][15]

Experimental values[edit]

The thermal conductivities of common substances span at least four orders of magnitude.[16] Gases generally have low thermal conductivity, and pure metals have high thermal conductivity. For example, under standard conditions the thermal conductivity of copper is over 10000 times that of air.

Of all materials, allotropes of carbon, such as graphite and diamond, are usually credited with having the highest thermal conductivities at room temperature.[17] The thermal conductivity of natural diamond at room temperature is several times higher than that of a highly conductive metal such as copper (although the precise value varies depending on the diamond type).[18]

Thermal conductivities of selected substances are tabulated below; an expanded list can be found in the list of thermal conductivities. These values are illustrative estimates only, as they do not account for measurement uncertainties or variability in material definitions.

| Substance | Thermal conductivity (W·m−1·K−1) | Temperature (°C) |

|---|---|---|

| Air[19] | 0.026 | 25 |

| Styrofoam[20] | 0.033 | 25 |

| Water[21] | 0.6089 | 26.85 |

| Concrete[21] | 0.92 | – |

| Copper[21] | 384.1 | 18.05 |

| Natural diamond[18] | 895–1350 | 26.85 |

Influencing factors[edit]

Temperature[edit]

The effect of temperature on thermal conductivity is different for metals and nonmetals. In metals, heat conductivity is primarily due to free electrons. Following the Wiedemann–Franz law, thermal conductivity of metals is approximately proportional to the absolute temperature (in kelvins) times electrical conductivity. In pure metals the electrical conductivity decreases with increasing temperature and thus the product of the two, the thermal conductivity, stays approximately constant. However, as temperatures approach absolute zero, the thermal conductivity decreases sharply.[22] In alloys the change in electrical conductivity is usually smaller and thus thermal conductivity increases with temperature, often proportionally to temperature. Many pure metals have a peak thermal conductivity between 2 K and 10 K.

On the other hand, heat conductivity in nonmetals is mainly due to lattice vibrations (phonons). Except for high-quality crystals at low temperatures, the phonon mean free path is not reduced significantly at higher temperatures. Thus, the thermal conductivity of nonmetals is approximately constant at high temperatures. At low temperatures well below the Debye temperature, thermal conductivity decreases, as does the heat capacity, due to carrier scattering from defects.[22]

Chemical phase[edit]

When a material undergoes a phase change (e.g. from solid to liquid), the thermal conductivity may change abruptly. For instance, when ice melts to form liquid water at 0 °C, the thermal conductivity changes from 2.18 W/(m⋅K) to 0.56 W/(m⋅K).[23]

Even more dramatically, the thermal conductivity of a fluid diverges in the vicinity of the vapor-liquid critical point.[24]

Thermal anisotropy[edit]

Some substances, such as non-cubic crystals, can exhibit different thermal conductivities along different crystal axes. Sapphire is a notable example of variable thermal conductivity based on orientation and temperature, with 35 W/(m⋅K) along the c axis and 32 W/(m⋅K) along the a axis.[25]

Wood generally conducts better along the grain than across it. Other examples of materials where the thermal conductivity varies with direction are metals that have undergone heavy cold pressing, laminated materials, cables, the materials used for the Space Shuttle thermal protection system, and fiber-reinforced composite structures.[26]

When anisotropy is present, the direction of heat flow may differ from the direction of the thermal gradient.

Electrical conductivity[edit]

In metals, thermal conductivity is approximately correlated with electrical conductivity according to the Wiedemann–Franz law, as freely moving valence electrons transfer not only electric current but also heat energy. However, the general correlation between electrical and thermal conductance does not hold for other materials, due to the increased importance of phonon carriers for heat in non-metals. Highly electrically conductive silver is less thermally conductive than diamond, which is an electrical insulator but conducts heat via phonons due to its orderly array of atoms.

Magnetic field[edit]

The influence of magnetic fields on thermal conductivity is known as the thermal Hall effect or Righi–Leduc effect.

Gaseous phases[edit]

Exhaust system components with ceramic coatings having a low thermal conductivity reduce heating of nearby sensitive components

In the absence of convection, air and other gases are good insulators. Therefore, many insulating materials function simply by having a large number of gas-filled pockets which obstruct heat conduction pathways. Examples of these include expanded and extruded polystyrene (popularly referred to as «styrofoam») and silica aerogel, as well as warm clothes. Natural, biological insulators such as fur and feathers achieve similar effects by trapping air in pores, pockets, or voids.

Low density gases, such as hydrogen and helium typically have high thermal conductivity. Dense gases such as xenon and dichlorodifluoromethane have low thermal conductivity. An exception, sulfur hexafluoride, a dense gas, has a relatively high thermal conductivity due to its high heat capacity. Argon and krypton, gases denser than air, are often used in insulated glazing (double paned windows) to improve their insulation characteristics.

The thermal conductivity through bulk materials in porous or granular form is governed by the type of gas in the gaseous phase, and its pressure.[27] At low pressures, the thermal conductivity of a gaseous phase is reduced, with this behaviour governed by the Knudsen number, defined as

Isotopic purity[edit]

The thermal conductivity of a crystal can depend strongly on isotopic purity, assuming other lattice defects are negligible. A notable example is diamond: at a temperature of around 100 K the thermal conductivity increases from 10,000 W·m−1·K−1 for natural type IIa diamond (98.9% 12C), to 41,000 for 99.9% enriched synthetic diamond. A value of 200,000 is predicted for 99.999% 12C at 80 K, assuming an otherwise pure crystal.[28] The thermal conductivity of 99% isotopically enriched cubic boron nitride is ~ 1400 W·m−1·K−1,[29] which is 90% higher than that of natural boron nitride.

Molecular origins[edit]

The molecular mechanisms of thermal conduction vary among different materials, and in general depend on details of the microscopic structure and molecular interactions. As such, thermal conductivity is difficult to predict from first-principles. Any expressions for thermal conductivity which are exact and general, e.g. the Green-Kubo relations, are difficult to apply in practice, typically consisting of averages over multiparticle correlation functions.[30] A notable exception is a monatomic dilute gas, for which a well-developed theory exists expressing thermal conductivity accurately and explicitly in terms of molecular parameters.

In a gas, thermal conduction is mediated by discrete molecular collisions. In a simplified picture of a solid, thermal conduction occurs by two mechanisms: 1) the migration of free electrons and 2) lattice vibrations (phonons). The first mechanism dominates in pure metals and the second in non-metallic solids. In liquids, by contrast, the precise microscopic mechanisms of thermal conduction are poorly understood.[31]

Gases[edit]

In a simplified model of a dilute monatomic gas, molecules are modeled as rigid spheres which are in constant motion, colliding elastically with each other and with the walls of their container. Consider such a gas at temperature

where

To incorporate more complex interparticle interactions, a systematic approach is necessary. One such approach is provided by Chapman–Enskog theory, which derives explicit expressions for thermal conductivity starting from the Boltzmann equation. The Boltzmann equation, in turn, provides a statistical description of a dilute gas for generic interparticle interactions. For a monatomic gas, expressions for

where

where

For gases whose molecules are not spherically symmetric, the expression

The entirety of this section assumes the mean free path

Liquids[edit]

The exact mechanisms of thermal conduction are poorly understood in liquids: there is no molecular picture which is both simple and accurate. An example of a simple but very rough theory is that of Bridgman, in which a liquid is ascribed a local molecular structure similar to that of a solid, i.e. with molecules located approximately on a lattice. Elementary calculations then lead to the expression

where

Metals[edit]

For metals at low temperatures the heat is carried mainly by the free electrons. In this case the mean velocity is the Fermi velocity which is temperature independent. The mean free path is determined by the impurities and the crystal imperfections which are temperature independent as well. So the only temperature-dependent quantity is the heat capacity c, which, in this case, is proportional to T. So

with k0 a constant. For pure metals, k0 is large, so the thermal conductivity is high. At higher temperatures the mean free path is limited by the phonons, so the thermal conductivity tends to decrease with temperature. In alloys the density of the impurities is very high, so l and, consequently k, are small. Therefore, alloys, such as stainless steel, can be used for thermal insulation.

Lattice waves[edit]

Heat transport in both amorphous and crystalline dielectric solids is by way of elastic vibrations of the lattice (i.e., phonons). This transport mechanism is theorized to be limited by the elastic scattering of acoustic phonons at lattice defects. This has been confirmed by the experiments of Chang and Jones on commercial glasses and glass ceramics, where the mean free paths were found to be limited by «internal boundary scattering» to length scales of 10−2 cm to 10−3 cm.[39][40]

The phonon mean free path has been associated directly with the effective relaxation length for processes without directional correlation. If Vg is the group velocity of a phonon wave packet, then the relaxation length

where t is the characteristic relaxation time. Since longitudinal waves have a much greater phase velocity than transverse waves,[41] Vlong is much greater than Vtrans, and the relaxation length or mean free path of longitudinal phonons will be much greater. Thus, thermal conductivity will be largely determined by the speed of longitudinal phonons.[39][42]

Regarding the dependence of wave velocity on wavelength or frequency (dispersion), low-frequency phonons of long wavelength will be limited in relaxation length by elastic Rayleigh scattering. This type of light scattering from small particles is proportional to the fourth power of the frequency. For higher frequencies, the power of the frequency will decrease until at highest frequencies scattering is almost frequency independent. Similar arguments were subsequently generalized to many glass forming substances using Brillouin scattering.[43][44][45][46]

Phonons in the acoustical branch dominate the phonon heat conduction as they have greater energy dispersion and therefore a greater distribution of phonon velocities. Additional optical modes could also be caused by the presence of internal structure (i.e., charge or mass) at a lattice point; it is implied that the group velocity of these modes is low and therefore their contribution to the lattice thermal conductivity λL (

Each phonon mode can be split into one longitudinal and two transverse polarization branches. By extrapolating the phenomenology of lattice points to the unit cells it is seen that the total number of degrees of freedom is 3pq when p is the number of primitive cells with q atoms/unit cell. From these only 3p are associated with the acoustic modes, the remaining 3p(q − 1) are accommodated through the optical branches. This implies that structures with larger p and q contain a greater number of optical modes and a reduced λL.

From these ideas, it can be concluded that increasing crystal complexity, which is described by a complexity factor CF (defined as the number of atoms/primitive unit cell), decreases λL.[48][failed verification] This was done by assuming that the relaxation time τ decreases with increasing number of atoms in the unit cell and then scaling the parameters of the expression for thermal conductivity in high temperatures accordingly.[47]

Describing anharmonic effects is complicated because an exact treatment as in the harmonic case is not possible, and phonons are no longer exact eigensolutions to the equations of motion. Even if the state of motion of the crystal could be described with a plane wave at a particular time, its accuracy would deteriorate progressively with time. Time development would have to be described by introducing a spectrum of other phonons, which is known as the phonon decay. The two most important anharmonic effects are the thermal expansion and the phonon thermal conductivity.

Only when the phonon number ‹n› deviates from the equilibrium value ‹n›0, can a thermal current arise as stated in the following expression

where v is the energy transport velocity of phonons. Only two mechanisms exist that can cause time variation of ‹n› in a particular region. The number of phonons that diffuse into the region from neighboring regions differs from those that diffuse out, or phonons decay inside the same region into other phonons. A special form of the Boltzmann equation

states this. When steady state conditions are assumed the total time derivate of phonon number is zero, because the temperature is constant in time and therefore the phonon number stays also constant. Time variation due to phonon decay is described with a relaxation time (τ) approximation

which states that the more the phonon number deviates from its equilibrium value, the more its time variation increases. At steady state conditions and local thermal equilibrium are assumed we get the following equation

Using the relaxation time approximation for the Boltzmann equation and assuming steady-state conditions, the phonon thermal conductivity λL can be determined. The temperature dependence for λL originates from the variety of processes, whose significance for λL depends on the temperature range of interest. Mean free path is one factor that determines the temperature dependence for λL, as stated in the following equation

where Λ is the mean free path for phonon and

At low temperatures (< 10 K) the anharmonic interaction does not influence the mean free path and therefore, the thermal resistivity is determined only from processes for which q-conservation does not hold. These processes include the scattering of phonons by crystal defects, or the scattering from the surface of the crystal in case of high quality single crystal. Therefore, thermal conductance depends on the external dimensions of the crystal and the quality of the surface. Thus, temperature dependence of λL is determined by the specific heat and is therefore proportional to T3.[49]

Phonon quasimomentum is defined as ℏq and differs from normal momentum because it is only defined within an arbitrary reciprocal lattice vector. At higher temperatures (10 K < T < Θ), the conservation of energy

Therefore, these processes are also known as Umklapp (U) processes and can only occur when phonons with sufficiently large q-vectors are excited, because unless the sum of q2 and q3 points outside of the Brillouin zone the momentum is conserved and the process is normal scattering (N-process). The probability of a phonon to have energy E is given by the Boltzmann distribution

Therefore, these phonons have to possess energy of

At high temperatures (T > Θ), the mean free path and therefore λL has a temperature dependence T−1, to which one arrives from formula

Thermal conductivity is usually described by the Boltzmann equation with the relaxation time approximation in which phonon scattering is a limiting factor. Another approach is to use analytic models or molecular dynamics or Monte Carlo based methods to describe thermal conductivity in solids.

Short wavelength phonons are strongly scattered by impurity atoms if an alloyed phase is present, but mid and long wavelength phonons are less affected. Mid and long wavelength phonons carry significant fraction of heat, so to further reduce lattice thermal conductivity one has to introduce structures to scatter these phonons. This is achieved by introducing interface scattering mechanism, which requires structures whose characteristic length is longer than that of impurity atom. Some possible ways to realize these interfaces are nanocomposites and embedded nanoparticles or structures.

Prediction[edit]

Because thermal conductivity depends continuously on quantities like temperature and material composition, it cannot be fully characterized by a finite number of experimental measurements. Predictive formulas become necessary if experimental values are not available under the physical conditions of interest. This capability is important in thermophysical simulations, where quantities like temperature and pressure vary continuously with space and time, and may encompass extreme conditions inaccessible to direct measurement.[50]

In fluids[edit]

For the simplest fluids, such as dilute monatomic gases and their mixtures, ab initio quantum mechanical computations can accurately predict thermal conductivity in terms of fundamental atomic properties—that is, without reference to existing measurements of thermal conductivity or other transport properties.[51] This method uses Chapman-Enskog theory to evaluate a low-density expansion of thermal conductivity. Chapman-Enskog theory, in turn, takes fundamental intermolecular potentials as input, which are computed ab initio from a quantum mechanical description.

For most fluids, such high-accuracy, first-principles computations are not feasible. Rather, theoretical or empirical expressions must be fit to existing thermal conductivity measurements. If such an expression is fit to high-fidelity data over a large range of temperatures

and pressures, then it is called a «reference correlation» for that material. Reference correlations have been published for many pure materials; examples are carbon dioxide, ammonia, and benzene.[52][53][54] Many of these cover temperature and pressure ranges that encompass gas, liquid, and supercritical phases.

Thermophysical modeling software often relies on reference correlations for predicting thermal conductivity at user-specified temperature and pressure. These correlations may be proprietary. Examples are REFPROP[55] (proprietary) and CoolProp[56] (open-source).

Thermal conductivity can also be computed using the Green-Kubo relations, which express transport coefficients in terms of the statistics of molecular trajectories.[57] The advantage of these expressions is that they are formally exact and valid for general systems. The disadvantage is that they require detailed knowledge of particle trajectories, available only in computationally expensive simulations such as molecular dynamics. An accurate model for interparticle interactions is also required, which may be difficult to obtain for complex molecules.[58]

In solids[edit]

|

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (January 2022) |

See also[edit]

- Copper in heat exchangers

- Heat pump

- Heat transfer

- Heat transfer mechanisms

- Insulated pipe

- Interfacial thermal resistance

- Laser flash analysis

- List of thermal conductivities

- Phase-change material

- R-value (insulation)

- Specific heat capacity

- Thermal bridge

- Thermal conductance quantum

- Thermal contact conductance

- Thermal diffusivity

- Thermal effusivity

- Thermal entrance length

- Thermal interface material

- Thermal diode

- Thermal resistance

- Thermistor

- Thermocouple

- Thermodynamics

- Thermal conductivity measurement

- Refractory metals

References[edit]

Notes[edit]

- ^ 1 Btu/(h⋅ft⋅°F) = 1.730735 W/(m⋅K)

- ^ R-values and U-values quoted in the US (based on the inch-pound units of measurement) do not correspond with and are not compatible with those used outside the US (based on the SI units of measurement).

Citations[edit]

- ^ Bird, Stewart & Lightfoot 2006, p. 266.

- ^ Bird, Stewart & Lightfoot 2006, pp. 266–267.

- ^ Holman, J.P. (1997), Heat Transfer (8th ed.), McGraw Hill, p. 2, ISBN 0-07-844785-2

- ^ Bejan, Adrian (1993), Heat Transfer, John Wiley & Sons, pp. 10–11, ISBN 0-471-50290-1

- ^ Bird, Stewart & Lightfoot 2006, p. 267.

- ^ a b Bejan, p. 34

- ^ Bird, Stewart & Lightfoot 2006, p. 305.

- ^ Gray, H.J.; Isaacs, Alan (1975). A New Dictionary of Physics (2nd ed.). Longman Group Limited. p. 251. ISBN 0582322421.

- ^ ASTM C168 − 15a Standard Terminology Relating to Thermal Insulation.

- ^ «Thermal Performance: Thermal Mass in Buildings». greenspec.co.uk. Retrieved 2022-09-13.

- ^ Bird, Stewart & Lightfoot 2006, p. 268.

- ^ Incropera, Frank P.; DeWitt, David P. (1996), Fundamentals of heat and mass transfer (4th ed.), Wiley, pp. 50–51, ISBN 0-471-30460-3

- ^

Perry, R. H.; Green, D. W., eds. (1997). Perry’s Chemical Engineers’ Handbook (7th ed.). McGraw-Hill. Table 1–4. ISBN 978-0-07-049841-9. - ^ Daniel V. Schroeder (2000), An Introduction to Thermal Physics, Addison Wesley, p. 39, ISBN 0-201-38027-7

- ^ Chapman, Sydney; Cowling, T.G. (1970), The Mathematical Theory of Non-Uniform Gases (3rd ed.), Cambridge University Press, p. 248

- ^ Heap, Michael J.; Kushnir, Alexandra R.L.; Vasseur, Jérémie; Wadsworth, Fabian B.; Harlé, Pauline; Baud, Patrick; Kennedy, Ben M.; Troll, Valentin R.; Deegan, Frances M. (2020-06-01). «The thermal properties of porous andesite». Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research. 398: 106901. Bibcode:2020JVGR..39806901H. doi:10.1016/j.jvolgeores.2020.106901. ISSN 0377-0273. S2CID 219060797.

- ^ An unlikely competitor for diamond as the best thermal conductor, Phys.org news (July 8, 2013).

- ^ a b «Thermal Conductivity in W cm−1 K−1 of Metals and Semiconductors as a Function of Temperature», in CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics, 99th Edition (Internet Version 2018), John R. Rumble, ed., CRC Press/Taylor & Francis, Boca Raton, FL.

- ^ Lindon C. Thomas (1992), Heat Transfer, Prentice Hall, p. 8, ISBN 978-0133849424

- ^ «Thermal Conductivity of common Materials and Gases». www.engineeringtoolbox.com.

- ^ a b c Bird, Stewart & Lightfoot 2006, pp. 270–271.

- ^ a b Hahn, David W.; Özişik, M. Necati (2012). Heat conduction (3rd ed.). Hoboken, N.J.: Wiley. p. 5. ISBN 978-0-470-90293-6.

- ^ Ramires, M. L. V.; Nieto de Castro, C. A.; Nagasaka, Y.; Nagashima, A.; Assael, M. J.; Wakeham, W. A. (July 6, 1994). «Standard reference data for the thermal conductivity of water». Journal of Physical and Chemical Reference Data. NIST. 24 (3): 1377–1381. doi:10.1063/1.555963. Retrieved 25 May 2017.

- ^ Millat, Jürgen; Dymond, J.H.; Nieto de Castro, C.A. (2005). Transport properties of fluids: their correlation, prediction, and estimation. Cambridge New York: IUPAC/Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-02290-3.

- ^

«Sapphire, Al2O3«. Almaz Optics. Retrieved 2012-08-15. - ^ Hahn, David W.; Özişik, M. Necati (2012). Heat conduction (3rd ed.). Hoboken, N.J.: Wiley. p. 614. ISBN 978-0-470-90293-6.

- ^ a b Dai, W.; et al. (2017). «Influence of gas pressure on the effective thermal conductivity of ceramic breeder pebble beds». Fusion Engineering and Design. 118: 45–51. doi:10.1016/j.fusengdes.2017.03.073.

- ^ Wei, Lanhua; Kuo, P. K.; Thomas, R. L.; Anthony, T. R.; Banholzer, W. F. (16 February 1993). «Thermal conductivity of isotopically modified single crystal diamond». Physical Review Letters. 70 (24): 3764–3767. Bibcode:1993PhRvL..70.3764W. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.70.3764. PMID 10053956.

- ^ Chen, Ke; Song, Bai; Ravichandran, Navaneetha K.; Zheng, Qiye; Chen, Xi; Lee, Hwijong; Sun, Haoran; Li, Sheng; Gamage, Geethal Amila Gamage Udalamatta; Tian, Fei; Ding, Zhiwei (2020-01-31). «Ultrahigh thermal conductivity in isotope-enriched cubic boron nitride». Science. 367 (6477): 555–559. Bibcode:2020Sci…367..555C. doi:10.1126/science.aaz6149. hdl:1721.1/127819. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 31919128. S2CID 210131908.

- ^ see, e.g., Balescu, Radu (1975), Equilibrium and Nonequilibrium Statistical Mechanics, John Wiley & Sons, pp. 674–675, ISBN 978-0-471-04600-4

- ^ Incropera, Frank P.; DeWitt, David P. (1996), Fundamentals of heat and mass transfer (4th ed.), Wiley, p. 47, ISBN 0-471-30460-3

- ^ Chapman, Sydney; Cowling, T.G. (1970), The Mathematical Theory of Non-Uniform Gases (3rd ed.), Cambridge University Press, pp. 100–101

- ^ a b Bird, Stewart & Lightfoot 2006, p. 275.

- ^ Chapman & Cowling, p. 167

- ^ a b Chapman & Cowling, p. 247

- ^ Chapman & Cowling, pp. 249-251

- ^ Bird, Stewart & Lightfoot 2006, p. 276.

- ^ Bird, Stewart & Lightfoot 2006, p. 279.

- ^ a b

Klemens, P.G. (1951). «The Thermal Conductivity of Dielectric Solids at Low Temperatures». Proceedings of the Royal Society of London A. 208 (1092): 108. Bibcode:1951RSPSA.208..108K. doi:10.1098/rspa.1951.0147. S2CID 136951686. - ^

Chang, G. K.; Jones, R. E. (1962). «Low-Temperature Thermal Conductivity of Amorphous Solids». Physical Review. 126 (6): 2055. Bibcode:1962PhRv..126.2055C. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.126.2055. - ^ Crawford, Frank S. (1968). Berkeley Physics Course: Vol. 3: Waves. McGraw-Hill. p. 215. ISBN 9780070048607.

- ^

Pomeranchuk, I. (1941). «Thermal conductivity of the paramagnetic dielectrics at low temperatures». Journal of Physics USSR. 4: 357. ISSN 0368-3400. - ^

Zeller, R. C.; Pohl, R. O. (1971). «Thermal Conductivity and Specific Heat of Non-crystalline Solids». Physical Review B. 4 (6): 2029. Bibcode:1971PhRvB…4.2029Z. doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.4.2029. - ^

Love, W. F. (1973). «Low-Temperature Thermal Brillouin Scattering in Fused Silica and Borosilicate Glass». Physical Review Letters. 31 (13): 822. Bibcode:1973PhRvL..31..822L. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.31.822. - ^

Zaitlin, M. P.; Anderson, M. C. (1975). «Phonon thermal transport in noncrystalline materials». Physical Review B. 12 (10): 4475. Bibcode:1975PhRvB..12.4475Z. doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.12.4475. - ^

Zaitlin, M. P.; Scherr, L. M.; Anderson, M. C. (1975). «Boundary scattering of phonons in noncrystalline materials». Physical Review B. 12 (10): 4487. Bibcode:1975PhRvB..12.4487Z. doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.12.4487. - ^ a b c d

Pichanusakorn, P.; Bandaru, P. (2010). «Nanostructured thermoelectrics». Materials Science and Engineering: R: Reports. 67 (2–4): 19–63. doi:10.1016/j.mser.2009.10.001. S2CID 46456426. - ^ Roufosse, Micheline; Klemens, P. G. (1973-06-15). «Thermal Conductivity of Complex Dielectric Crystals». Physical Review B. 7 (12): 5379–5386. Bibcode:1973PhRvB…7.5379R. doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.7.5379.

- ^ a b c d

Ibach, H.; Luth, H. (2009). Solid-State Physics: An Introduction to Principles of Materials Science. Springer. ISBN 978-3-540-93803-3. - ^ Puligheddu, Marcello; Galli, Giulia (2020-05-11). «Atomistic simulations of the thermal conductivity of liquids». Physical Review Materials. American Physical Society (APS). 4 (5): 053801. Bibcode:2020PhRvM…4e3801P. doi:10.1103/physrevmaterials.4.053801. ISSN 2475-9953. OSTI 1631591. S2CID 219408529.

- ^ Sharipov, Felix; Benites, Victor J. (2020-07-01). «Transport coefficients of multi-component mixtures of noble gases based on ab initio potentials: Viscosity and thermal conductivity». Physics of Fluids. AIP Publishing. 32 (7): 077104. arXiv:2006.08687. Bibcode:2020PhFl…32g7104S. doi:10.1063/5.0016261. ISSN 1070-6631. S2CID 219708359.

- ^ Huber, M. L.; Sykioti, E. A.; Assael, M. J.; Perkins, R. A. (2016). «Reference Correlation of the Thermal Conductivity of Carbon Dioxide from the Triple Point to 1100 K and up to 200 MPa». Journal of Physical and Chemical Reference Data. AIP Publishing. 45 (1): 013102. Bibcode:2016JPCRD..45a3102H. doi:10.1063/1.4940892. ISSN 0047-2689. PMC 4824315. PMID 27064300.

- ^ Monogenidou, S. A.; Assael, M. J.; Huber, M. L. (2018). «Reference Correlation for the Thermal Conductivity of Ammonia from the Triple-Point Temperature to 680 K and Pressures up to 80 MPa». Journal of Physical and Chemical Reference Data. AIP Publishing. 47 (4): 043101. Bibcode:2018JPCRD..47d3101M. doi:10.1063/1.5053087. ISSN 0047-2689. S2CID 105753612.

- ^ Assael, M. J.; Mihailidou, E. K.; Huber, M. L.; Perkins, R. A. (2012). «Reference Correlation of the Thermal Conductivity of Benzene from the Triple Point to 725 K and up to 500 MPa». Journal of Physical and Chemical Reference Data. AIP Publishing. 41 (4): 043102. Bibcode:2012JPCRD..41d3102A. doi:10.1063/1.4755781. ISSN 0047-2689.

- ^ «NIST Reference Fluid Thermodynamic and Transport Properties Database (REFPROP): Version 10». Nist. 2018-01-01. Retrieved 2021-12-23.

- ^ Bell, Ian H.; Wronski, Jorrit; Quoilin, Sylvain; Lemort, Vincent (2014-01-27). «Pure and Pseudo-pure Fluid Thermophysical Property Evaluation and the Open-Source Thermophysical Property Library CoolProp». Industrial & Engineering Chemistry Research. American Chemical Society (ACS). 53 (6): 2498–2508. doi:10.1021/ie4033999. ISSN 0888-5885. PMC 3944605. PMID 24623957.

- ^ Evans, Denis J.; Morriss, Gary P. (2007). Statistical Mechanics of Nonequilibrium Liquids. ANU Press. ISBN 9781921313226. JSTOR j.ctt24h99q.

- ^ Maginn, Edward J.; Messerly, Richard A.; Carlson, Daniel J.; Roe, Daniel R.; Elliott, J. Richard (2019). «Best Practices for Computing Transport Properties 1. Self-Diffusivity and Viscosity from Equilibrium Molecular Dynamics [Article v1.0]». Living Journal of Computational Molecular Science. University of Colorado at Boulder. 1 (1). doi:10.33011/livecoms.1.1.6324. ISSN 2575-6524. S2CID 104357320.

Sources[edit]

- Bird, R.B.; Stewart, W.E.; Lightfoot, E.N. (2006). Transport Phenomena. Transport Phenomena. Vol. 1. Wiley. ISBN 978-0-470-11539-8.

Further reading[edit]

Undergraduate-level texts (engineering)[edit]

- Bird, R. Byron; Stewart, Warren E.; Lightfoot, Edwin N. (2007), Transport Phenomena (2nd ed.), John Wiley & Sons, Inc., ISBN 978-0-470-11539-8. A standard, modern reference.

- Incropera, Frank P.; DeWitt, David P. (1996), Fundamentals of heat and mass transfer (4th ed.), Wiley, ISBN 0-471-30460-3

- Bejan, Adrian (1993), Heat Transfer, John Wiley & Sons, ISBN 0-471-50290-1

- Holman, J.P. (1997), Heat Transfer (8th ed.), McGraw Hill, ISBN 0-07-844785-2

- Callister, William D. (2003), «Appendix B», Materials Science and Engineering — An Introduction, John Wiley & Sons, ISBN 0-471-22471-5

Undergraduate-level texts (physics)[edit]

- Halliday, David; Resnick, Robert; & Walker, Jearl (1997). Fundamentals of Physics (5th ed.). John Wiley and Sons, New York ISBN 0-471-10558-9. An elementary treatment.

- Daniel V. Schroeder (1999), An Introduction to Thermal Physics, Addison Wesley, ISBN 978-0-201-38027-9. A brief, intermediate-level treatment.

- Reif, F. (1965), Fundamentals of Statistical and Thermal Physics, McGraw-Hill. An advanced treatment.

Graduate-level texts[edit]

- Balescu, Radu (1975), Equilibrium and Nonequilibrium Statistical Mechanics, John Wiley & Sons, ISBN 978-0-471-04600-4

- Chapman, Sydney; Cowling, T.G. (1970), The Mathematical Theory of Non-Uniform Gases (3rd ed.), Cambridge University Press. A very advanced but classic text on the theory of transport processes in gases.

- Reid, C. R., Prausnitz, J. M., Poling B. E., Properties of gases and liquids, IV edition, Mc Graw-Hill, 1987

- Srivastava G. P (1990), The Physics of Phonons. Adam Hilger, IOP Publishing Ltd, Bristol

External links[edit]

- Thermopedia THERMAL CONDUCTIVITY

- Contribution of Interionic Forces to the Thermal Conductivity of Dilute Electrolyte Solutions The Journal of Chemical Physics 41, 3924 (1964)

- The importance of Soil Thermal Conductivity for power companies

- Thermal Conductivity of Gas Mixtures in Chemical Equilibrium. II The Journal of Chemical Physics 32, 1005 (1960)

Содержание

- Характеристика показателя

- Как определить теплопотери

- Коэффициент теплопроводности

- Пример из практики

- Стройматериалы для наружных стен

- Утеплители для стен

- Теплопроводность: понятие и теория

- От чего зависит величина теплопроводности?

- Использование значений теплопроводности на практике

- Особенности теплопроводности готового строения

- Разновидности утепления конструкций

- Как определить коэффициенты теплопроводности строительных материалов: таблица

- Полезные рекомендации

Раз мне не нравятся теплоизоляционные материалы, что сплошь и рядом впаривают фирмачи, я вынужден искать им замену более экологичную и дешевую. Но вот вопрос: как определить, какой толщины слой должен быть? Каков коэффициент теплопроводности, например, у опилкобетона той или другой марки? А если вообще насыпной?

Фирмачи – они хоть и врут часто и без меры, но хоть ориентировочно можно определиться. А с опилом, с соломой, с тростником или камышом – практически никто ничего вразумительного сказать не может. Оно и понятно: измерить коэффициент теплопроводности – задача не из легких и далеко не из дешевых.

Ну да ничего, у нас золотое правило есть: голь на выдумки хитра! Проанализировав по СНиП II-3-79 различные материалы-теплоизоляторы, я вычертил график соответствия между плотностью материала и его коэффициентом теплопроводности.

Так что, теперь не надо больше ломать голову. Просто взвесь материал в сухом состоянии, определи его плотность (сколько килограммов в кубометре), и по графику можно с достаточной точностью узнать его коэффициент теплопроводности. Для сухого состояния!!

Эврика? Да ничего я нового не открыл опять же. Это соотношение давно известно, и если настойчиво покопаться в рунете, то можно найти и подтверждение, и не одно. Только это если настойчиво. Мало кто из фирмачей имеет желание публиковать такие сведения. Ну, дык, понятно.

Какими бы ни были масштабы строительства, первым делом разрабатывается проект. В чертежах отражается не только геометрия строения, но и расчет главных теплотехнических характеристик. Для этого надо знать теплопроводность строительных материалов. Главная цель строительства заключается в сооружении долговечных сооружений, прочных конструкций, в которых комфортно без избыточных затрат на отопление. В связи с этим крайне важно знание коэффициентов теплопроводности материалов.

Характеристика показателя

Под термином теплопроводность понимается передача тепловой энергии от более нагретых предметов к менее нагретым. Обмен идет, пока не наступит температурного равновесия.

Теплопередача определяется отрезком времени, в течение которого температура в помещениях находится в соответствии с температурой окружающей среды. Чем меньше этот интервал, тем больше проводимость тепла стройматериала.

Для характеристики проводимости тепла используется понятие коэффициента теплопроводности, показывающего, сколько тепла за такое-то время проходит через такую-то площадь поверхности. Чем этот показатель выше, тем больше теплообмен, и постройка остывает гораздо быстрее. Таким образом, при возведении сооружений рекомендуется использовать стройматериалы с минимальной проводимостью тепла.

В этом видео вы узнаете о теплопроводности строительных материалов:

Как определить теплопотери

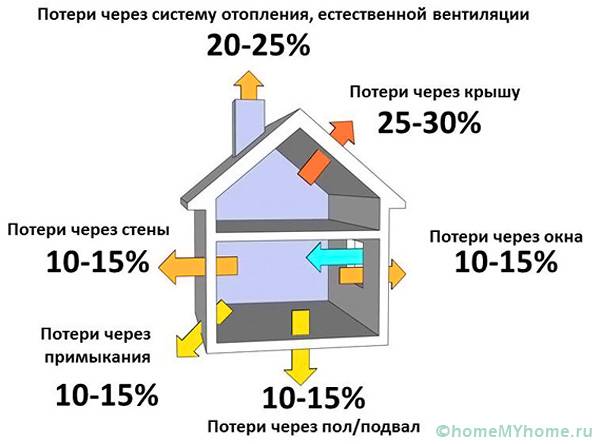

Главные элементы здания, через которые уходит тепло:

Уровень теплопотери определяется с помощью тепловизора. О самых трудных участках говорит красный цвет, о меньших потерях тепла скажет желтый и зеленый. Зоны, где потери наименьшие, выделяются синим. Значение теплопроводности определяется в лабораторных условиях, и материалу выдается сертификат качества.

Значение проводимости тепла зависит от таких параметров:

- Пористость. Поры говорят о неоднородности структуры. Когда через них проходит тепло, охлаждение будет минимальным.

- Влажность. Высокий уровень влажности провоцирует вытеснение сухого воздуха капельками жидкости из пор, из-за чего значение увеличивается многократно.

- Плотность. Большая плотность способствует более активному взаимодействию частиц. В итоге теплообмен и уравновешивание температур протекает быстрее.

Коэффициент теплопроводности

В доме теплопотери неизбежны, а происходят они, когда за окном температура ниже, чем в помещениях. Интенсивность является переменной величиной и зависит от многих факторов, основные из которых следующие:

- Площадь поверхностей, участвующих в теплообмене.

- Показатель теплопроводности стройматериалов и элементов здания.

- Разница температур.

Для обозначения коэффициента теплопроводности стройматериалов используют греческую букву λ. Единица измерения – Вт/(м×°C). Расчет производится на 1 м² стены метровой толщины. Здесь принимается разница температур в 1°C.

Пример из практики

Условно материалы делятся на теплоизоляционные и конструкционные. Последние имеют наивысшую теплопроводность, из них строят стены, перекрытия, другие ограждения. По таблице материалов, при постройке стен из железобетона для обеспечения малого теплообмена с окружающей средой толщина их должна составлять примерно 6 м. Но тогда строение будет громоздким и дорогостоящим.

В случае неправильного расчета теплопроводности при проектировании жильцы будущего дома будут довольствоваться лишь 10% тепла от энергоносителей. Потому дома из стандартных стройматериалов рекомендуется утеплять дополнительно.

При выполнении правильной гидроизоляции утеплителя большая влажность не влияет на качество теплоизоляции, и сопротивление строения теплообмену станет гораздо более высоким.

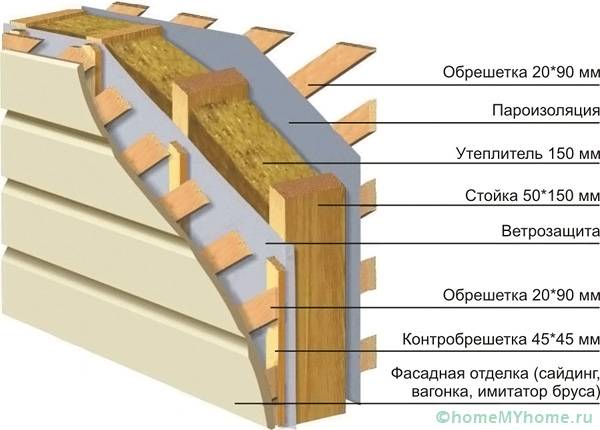

Наиболее распространенный вариант – сочетание несущей конструкции из высокопрочных материалов с дополнительной теплоизоляцией. Например:

- Каркасный дом. Утеплитель укладывается между стойками. Иногда при небольшом снижении теплообмена требуется дополнительное утепление снаружи главного каркаса.

- Сооружение из стандартных материалов. Когда стены кирпичные или шлакоблочные, утепление производится снаружи.

Стройматериалы для наружных стен

Стены сегодня возводятся из разных материалов, однако популярнейшими остаются: дерево, кирпич и строительные блоки. Главным образом отличаются плотность и проводимость тепла стройматериалов. Сравнительный анализ позволяет найти золотую середину в соотношении между этими параметрами. Чем плотность больше, тем больше несущая способность материала, а значит, всего сооружения. Но тепловое сопротивление становится меньше, то есть повышаются расходы на энергоносители. Обычно при меньшей плотности есть пористость.

Коэффициент теплопроводности и его плотность.

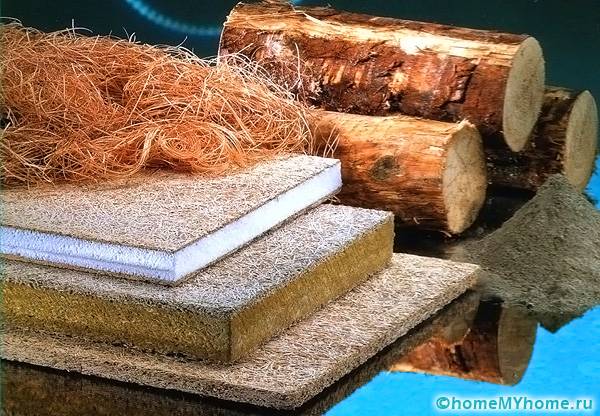

Утеплители для стен

Утеплители используются, когда не хватает тепловой сопротивляемости наружных стен. Обычно для создания комфортного микроклимата в помещениях достаточно толщины 5-10 см.

Значение коэффициента λ приводится в следующей таблице.

Теплопроводность измеряет способность материала пропускать тепло через себя. Она сильно зависит от состава и структуры. Плотные материалы, такие как металлы и камень, являются хорошими проводниками тепла, в то время как вещества с низкой плотностью, такие как газ и пористая изоляция, являются плохими проводниками.

Время чтения: 6 минут Нет времени?

Отправим материал вам на e-mail

Любые строительные работы начинаются с создания проекта. При этом планируется как расположение комнат в здании, так и рассчитываются главные теплотехнические показатели. От данных значений зависит, насколько будущая постройка будет теплой, долговечной и экономичной. Позволит определить теплопроводность строительных материалов – таблица, в которой отображены основные коэффициенты. Правильные расчеты являются гарантией удачного строительства и создания благоприятного микроклимата в помещении.

Чтобы дом был теплым без утеплителя потребуется определенная толщина стен, которая отличается в зависимости от вида материала

Теплопроводность: понятие и теория

Теплопроводность представляет собой процесс перемещения тепловой энергии от прогретых частей к холодным. Обменные процессы происходят до полного равновесия температурного значения.

Комфортный микроклимат в доме зависит от качественной теплоизоляции всех поверхностей

Процесс теплопередачи характеризуется промежутком времени, в течение которого выравниваются температурные значения. Чем больше времени проходит, тем ниже теплопроводность строительных материалов, свойства которых отображает таблица. Для определения данного показателя применяется такое понятие как коэффициент теплопроводности. Он определяет, какое количество тепловой энергии проходит через единицу площади определенной поверхности. Чем данный показатель больше, тем с большей скоростью будет остывать здание. Таблица теплопроводности нужна при проектировании защиты постройки от теплопотерь. При этом можно снизить эксплуатационный бюджет.

Потери тепла на разных участках постройки будут отличаться

Полезный совет! При постройке домов стоит использовать сырье с минимальной проводимостью тепла.

От чего зависит величина теплопроводности?

От множества факторов зависит значение теплопроводности строительных материалов. Таблица коэффициентов, представленная в нашем обзоре, это наглядно показывает.

Наглядный пример демонстрирует свойство теплопроводности

На данный показатель оказывают влияние следующие параметры:

- более высокая плотность способствует прочному взаимодействию частиц друг с другом. При этом уравновешивание температур производится более быстро. Чем плотнее материал, тем лучше пропускается тепло;

- пористость сырья свидетельствует о его неоднородности. При перемещении тепловой энергии через подобную структуру охлаждение будет небольшим. Внутри гранул находится только воздух, который обладает минимальным количеством коэффициента. Если поры маленькие, то при этом затрудняется передача тепла. Но повышается значение теплопроводность;

- при повышенной влажности и промокании стен здания показатель прохождения тепла будет выше.

Чем ниже показатель теплопроводности строительного сырья, тем уютнее и теплее в помещении

Использование значений теплопроводности на практике

Материалы, используемые в строительстве, могут быть конструкционными и теплоизолирующими.

Существует огромное количество материалов с теплоизолирующими свойствами

Самое большое значение теплопроводности у конструкционных материалов, которые используются при возведении перекрытий, стен и потолков. Если не использовать сырье с теплоизолирующими свойствами, то для сохранения тепла потребуется монтаж толстого слоя утеплителя для возведения стен.

Часто для утепления строений используются более простые материалы

Поэтому при возведении постройки стоит использовать дополнительные материалы. При этом значение имеет теплопроводность строительных материалов, таблица показывает все значения.

В некоторых случаях более эффективным считается утепление снаружи

Полезная информация! Для построек из древесины и пенобетона не обязательно использовать дополнительное утепление. Даже применяя низкопроводной материал, толщина сооружения не должна быть менее 50 см.

Особенности теплопроводности готового строения

Планируя проект будущего дома, нужно обязательно учесть возможные потери тепловой энергии. Большая часть тепла уходит через двери, окна, стены, крышу и полы.

В многоквартирных домах потери тепла будут отличаться по сравнению с частным строением

Если не выполнять расчеты по теплосбережению дома, то в помещении будет прохладно. Рекомендуется постройки из кирпича, бетона и камня дополнительно утеплять.

Утепление построек из бетона или камня повышает комфортные условия внутри здания

Полезный совет! Перед тем как утеплять жилище, необходимо продумать качественную гидроизоляцию. При этом даже повышенная влажность не повлияет на особенности теплоизоляции в помещении.

Разновидности утепления конструкций

Теплое здание получится при оптимальном сочетании конструкции из прочных материалов и качественного теплоизолирующего слоя. К подобным сооружениям можно отнести следующие:

- при возведении каркасной постройки, используемая древесина обеспечивает жесткость здания. Утеплитель прокладывается между стойками. В некоторых случаях применяется утепление снаружи здания;

Монтажные работы по утеплению каркасного сооружения требуют использования дополнительных конструктивных элементов

- здание из стандартных материалов: шлакоблоков или кирпича. При этом утепление часто проводится по наружной стороне.

Особенности монтажа теплоизолирующего материала с внутренней стороны

Как определить коэффициенты теплопроводности строительных материалов: таблица

Помогает определить коэффициент теплопроводности строительных материалов – таблица. В ней собраны все значения самых распространенных материалов. Используя подобные данные, можно рассчитать толщину стен и используемый утеплитель. Таблица значений теплопроводности:

Необходимые коэффициенты для самых различных материалов

Чтобы определить величину теплопроводности используются специальные ГОСТы. Значение данного показателя отличается в зависимости от вида бетона. Если материал имеет показатель 1,75, то пористый состав обладает значением 1,4. Если раствор выполнен с применением каменного щебня, то его значение 1,3.

Технические характеристики утеплителей для бетонных полов

О значении теплопроводности можно судить по сравнительным характеристикам

Полезные рекомендации

Потери через потолочные конструкции значительны для проживающих на последних этажах. К слабым участкам относится пространство между перекрытиями и стеной. Подобные участки считаются мостиками холода. Если над квартирой присутствует технический этаж, то при этом потери тепловой энергии меньше.

Выполняя утепление потолка на веранде или террасе, можно использовать более легкие стройматериалы

Утепление потолочного перекрытия на верхнем этаже производится снаружи. Также потолок можно утеплить внутри квартиры. Для этого применяется пенополистирол или теплоизоляционные плиты.

При утеплении потолка, стоит подобрать материал для пароизоляции и для гидроизоляции

Прежде чем утеплять любые поверхности, стоит узнать теплопроводность строительных материалов, таблица СНиПа поможет в этом. Утеплять напольное покрытие не так сложно как другие поверхности. В качестве утепляющих материалов применяются такие материалы как керамзит, стекловата ил пенополистирол.

Создание теплого пола требует особых знаний. Важно учитывать высоту и толщину материалов

Чтобы качественно утеплить квартиру на последних этажах, можно полноценно использовать возможности центрального отопления. При этом важно повысить отдачу тепло от радиаторов. Для этого стоит воспользоваться следующими советами:

- если какая-то часть батарей холодная, то требуется спустить воздух. При этом открывается специальный клапан;

- чтобы тепло проникало внутрь дома, на не обогревало стены, рекомендуется установить защитный экран с покрытием из фольги;

- для свободной циркуляции подогретого воздуха не стоит радиаторы загромождать мебелью или шторами;

- если снять декоративный экран, то теплоотдача увеличиться на 25 %.

Выбор качественных радиаторов позволяет лучше сберечь тепло в помещении

Тепловые потери через входные двери могут составлять до 10 %. При этом значительное количество тепла тратится на воздушные массы, которые поступают снаружи. Для устранения сквозняков надо переустановить изношенные уплотнители и щели, которые могут появиться между стеной и коробом. В данном случае дверное полотно можно обить, а щели заполнить с помощью монтажной пены.

Выбор утеплителя зависит от материала самой двери

Одним из основных источников теплопотерь являются окна. Если рамы старые, то появляются сквозняки. Через оконные проемы теряется около 35% тепловой энергии. Для качественного утепления применяются двухкамерные стеклопакеты. К другим способам относится утепление щелей монтажной пеной, оклейка мест стыков с рамой специальным уплотнителем и нанесение силиконового герметика. Правильное и комплексное утепление является гарантией комфортного и теплого дома, в котором не появиться плесень, сквозняки и холодный пол.

Экономьте время: отборные статьи каждую неделю по почте